With the summer break now upon us, it's safe to say 2025 is not a year on which Ferrari is going to look back with much fondness. Having come into the season atop a wave of fanfare and hype thanks to its 2024 constructors title near miss and the arrival of a certain seven-time world champion, the decision to pursue an all-new design philosophy ahead of this, the final year of the current rules cycle, has not paid dividends.

A pole and five podiums for Charles Leclerc have been the only discernible highlights, while Lewis Hamilton is currently enduring the longest podium drought of his entire career. The only respite being that sprint win in Shanghai. Bleak though this may seem, it is far from the Scuderia’s worst ever showing, when asked to identify Ferrari’s lowest ebb, younger fans will typically point to 2020, and while that is a good answer (no wins, three podiums and sixth in the constructors was nothing short of embarrassing) Ferrari’s true annus horribilis was 1980. The year Formula 1’s most successful team experienced its fastest ever fall from grace.

Before we begin, a disclaimer: the 1992 F92 A is technically the worst car Ferrari has ever produced, insofar as it had the biggest pace deficit to the front. However, the truculent 312 T5 has the dubious honour of yielding Ferrari’s lowest ever constructors’ championship finishing position.

No analysis of Ferrari’s woeful 1980 campaign is complete without a look back at 1977. A season remembered as one of the most transformational in F1 history, thanks to genius of Lotus boss Colin Chapman. One of the sport’s greatest lateral thinkers, Chapman was the first to experiment with ground effects, technology that continues to underpin the current generation of cars over four decades later.

The Lotus 78 had wider than average sidepods, supplemented by spring-loaded skirts that created an area of negative pressure when deployed, effectively sucking the car to the ground and providing unparalleled grip. They may have played second fiddle to Ferrari in 1977, but with five wins and seven pole positions, Lotus had made a statement with its ground effect technology. A statement that would soon become a manifesto. The 1978 Lotus 79 was a refinement of the theory and, in the capable hands of Mario Andretti, proved nigh on unstoppable. Pole and victory at the season opener in Argentina set the tone for the rest of the season, with Andretti claiming a five further wins en route to the driver’s championship.

On the other side of the garage, his teammate Ronnie Peterson maintained his part of the bargain by racking up four wins and five further podiums in a title bid that could well have gone his way, were it not for his untimely passing at the Italian Grand Prix. Although tainted by tragedy, Lotus’ double sent a very clear message: ground effects were here to stay and any team that wished to be taken seriously had to climb aboard the aerodynamic bandwagon. A warning all the frontrunners were quick to heed…except one.

In an inadvertent nod to the famed Enzo Ferrari quote ‘aerodynamics are for people who can’t build engines’ the Scuderia decided not to design an all-new car. Instead, famed engineer Mauro Forgheri was tasked with marrying this new aerodynamic formula with chassis architecture that dated back to 1975. Needless to say, such a marriage was essentially impossible.

The three-litre flat 12 engine that had underpinned much of the team’s recent success was low, wide and prevented any narrowing of the chassis. It also disrupted part of the area where the windswept underside should have been. As a result, the 1979 312 T4 made do with conventional aerodynamics. Fortunately for Ferrari, circumstance was on their side as Lotus failed to maintain their blistering form and fell out of title contention. The T4’s engine was both powerful, with around 515 horsepower on tap, and reliable with the team only recording one engine related DNF all season.

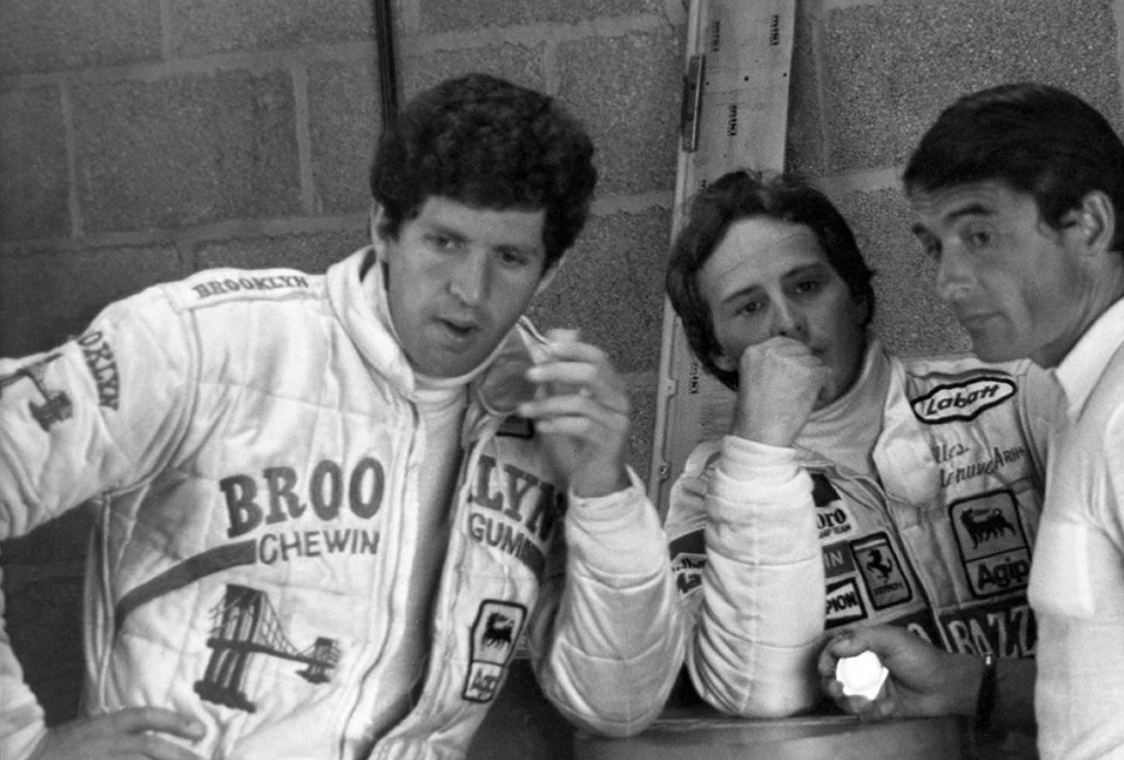

What’s more, Ferrari had the luxury of a near-perfect driver lineup. Having racked up seven grand prix wins with the likes of McLaren and Wolf, the unrelenting Jody Scheckter had all the makings of a world champion, as did his teammate: Ferrari protégé Gilles Villenueve. Hailed by many as the greatest driver never to win the world championship, the burgeoning Villeneuve had the measure of his teammate when it came to outright pace.

However, the Canadian was nothing if not intensely honourable. He respected Scheckter as a senior figure within the team and duly played the role of a reliable rear gunner. The combined powers of Villeneuve and Scheckter dominated the opening exchanges, winning four of the first seven grand prix and despite a mid-season wobble, Scheckter claimed what would turn out to be Ferrari’s last drivers’ championship of the 20th century. Villeneuve came home a close second with their joint efforts yielding a sixth constructor’s crown for the team. Ferrari had bucked the trend, in era that seemed to revolve around ground effects, the Scuderia stuck to its guns and came out on top regardless. Having helped the team to three drivers and four constructors’ titles, another evolution of the 312 T would surely be enough to keep them in contention, right?

Wrong.

Having held all the aces in 1979, Ferrari in 1980 served as a sobering demonstration of what happens when a competitive outfit stands still. The writing was on the wall in the back end of ’79. Ferrari may have taken the double, but Williams came on strong in the second half of the season. Introduced at round five in Spain, the FW08’s boxy side pods, ‘underwing’ panels and spring-loaded skirts made it the preeminent ground effect car of the time. While Ferrari’s early advantage would prove unassailable, Williams won five out of the last seven races.

For 1980, Williams unveiled the FW07 B, an upgraded variant that succeeded where its immediate predecessor had failed. With five wins and five further podiums, Alan Jones waltzed to the title as teammate Carlos Reutemann picked up a further victory en route to third. While Williams cruised to a maiden constructor’s crown, Ferrari were nowhere to be seen.

With ground effects now relied upon by virtually the entire grid, the new 312 T5 was now a relic of a bygone age. Slow, cumbersome and notoriously unreliable with ten DNF’s across the season, Ferrari were quick to abandon development of the T5 and focus all its efforts on 1981. As a result, there was little even its illustrious drivers could do to save face. While Villeneuve’s drive remained intact as he dragged the petulant T5 to results it didn’t deserve (though even he could only manage four points finishes with a best result of 5th), Scheckter admitted to a loss of motivation after claiming the ultimate prize the previous year. The off-colour Scheckter finished just nine of 1980’s 14 races, failed to outright qualify in Canada and ended the season 19th in the drivers’ standings with just two points to his name, in what remains the worst full season title defence in Formula 1 history.

Having enjoyed a near perfect campaign in 1979, Ferrari ended 1980 tenth in the constructor’s championship having managed just eight points all season. They’ve had some shockers since, of that there’s no doubt, but the lowly depths of 1980 have thankfully never been revisited by Formula 1’s most successful team.